BEIJING —

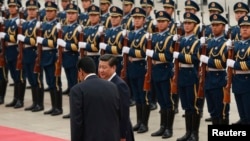

With ousted senior politician Bo Xilai jailed for life, Chinese President Xi Jinping has stamped his authority on the Communist Party by effectively warning he will not tolerate dissent as he seeks to push through tough economic reforms.

Bo was sentenced on Sunday after being found guilty on charges of corruption, taking bribes and abuse of power. Since all courts are controlled by the party the verdict was likely pre-ordained although a source with direct knowledge of the case told Reuters on Monday that Bo had filed an appeal.

“It's [like] killing one to warn a hundred,” a source with ties to the leadership told Reuters.

The ideological fractures exposed last year by Bo's fall from grace had hobbled Xi, forcing him to row back on an ambitious plan to rebalance the world's second largest economy, sources close to China's leadership have told Reuters.

The party's fear had been that Bo's supporters, who lauded him for the old-school leftist social welfare policies he championed as boss of the city of Chongqing, could remain a brake on reforms that favor private businesses and a greater reliance on market forces.

Xi needed the Bo affair settled because the next few weeks are critical for his government, which took office in March.

At a closed-door party plenum in November, Xi will push for more economic reforms and he needs unstinting support from the party's elite 200-member Central Committee.

The reforms Xi wants include opening up the banking sector to let in private players and enact interest rate reform, and introducing more competition in key industries dominated by state-owned giants, such as in the energy and telecommunications sectors, sources say.

Leftists are deeply suspicious of private enterprise and market reforms, believing they have led to the income inequality and the anything-goes economic growth that China grapples with today.

“For other senior officials, I think this is intimidating because the plenum is coming up,” said Zhang Lifan, a Beijing-based political commentator and historian.

Bo's wife also in jail

Bo had been expected to rise to the top of the party until his career unraveled last year following a murder scandal in which his wife, Gu Kailai, was convicted of poisoning a British businessman, Neil Heywood, who had been a family friend. She was given a suspended death sentence.

After his appointment as Chongqing party boss in 2007, the charismatic Bo, a “princeling” son of a late vice premier, turned the southwestern metropolis into a showcase of Mao-inspired “red” culture, as well as state-led economic growth. The leftists in the party flocked to his side.

Xi has been mindful of Bo's constituency and courted neo-leftists ahead of the trial - at the expense of reform-minded liberals.

Shortly before the trial, Xi paid his respects at a villa once used by Mao Zedong, and then gave a widely publicized speech calling Marxism a “must-study subject” for party members.

Xi, in a sense, already has sought to assume Bo's mantle as the hero of the left.

“Ideologically speaking, Xi's shift to the left has been quite dramatic,” said Li Weidong, a writer and former editor who has followed Bo's case closely. “Bo has been kicked to the side but his policies have remained.”

That is a path that may not be sustainable, Li added.

“It will create an effect of left-wing politics but right-wing economics, which will become a problem long-term.”

Still, Bo's verdict is unlikely to be a real deterrent to the rampant corruption Xi has sought to tackle, despite the party and state media playing up the angle that all are equal before the law.

“This case had little to do with corruption. It's a political case,” said Zhang Ming, a professor at Renmin University in Beijing.

Bo was sentenced on Sunday after being found guilty on charges of corruption, taking bribes and abuse of power. Since all courts are controlled by the party the verdict was likely pre-ordained although a source with direct knowledge of the case told Reuters on Monday that Bo had filed an appeal.

“It's [like] killing one to warn a hundred,” a source with ties to the leadership told Reuters.

The ideological fractures exposed last year by Bo's fall from grace had hobbled Xi, forcing him to row back on an ambitious plan to rebalance the world's second largest economy, sources close to China's leadership have told Reuters.

The party's fear had been that Bo's supporters, who lauded him for the old-school leftist social welfare policies he championed as boss of the city of Chongqing, could remain a brake on reforms that favor private businesses and a greater reliance on market forces.

Xi needed the Bo affair settled because the next few weeks are critical for his government, which took office in March.

At a closed-door party plenum in November, Xi will push for more economic reforms and he needs unstinting support from the party's elite 200-member Central Committee.

The reforms Xi wants include opening up the banking sector to let in private players and enact interest rate reform, and introducing more competition in key industries dominated by state-owned giants, such as in the energy and telecommunications sectors, sources say.

Leftists are deeply suspicious of private enterprise and market reforms, believing they have led to the income inequality and the anything-goes economic growth that China grapples with today.

“For other senior officials, I think this is intimidating because the plenum is coming up,” said Zhang Lifan, a Beijing-based political commentator and historian.

Bo's wife also in jail

Bo had been expected to rise to the top of the party until his career unraveled last year following a murder scandal in which his wife, Gu Kailai, was convicted of poisoning a British businessman, Neil Heywood, who had been a family friend. She was given a suspended death sentence.

After his appointment as Chongqing party boss in 2007, the charismatic Bo, a “princeling” son of a late vice premier, turned the southwestern metropolis into a showcase of Mao-inspired “red” culture, as well as state-led economic growth. The leftists in the party flocked to his side.

Xi has been mindful of Bo's constituency and courted neo-leftists ahead of the trial - at the expense of reform-minded liberals.

Shortly before the trial, Xi paid his respects at a villa once used by Mao Zedong, and then gave a widely publicized speech calling Marxism a “must-study subject” for party members.

Xi, in a sense, already has sought to assume Bo's mantle as the hero of the left.

“Ideologically speaking, Xi's shift to the left has been quite dramatic,” said Li Weidong, a writer and former editor who has followed Bo's case closely. “Bo has been kicked to the side but his policies have remained.”

That is a path that may not be sustainable, Li added.

“It will create an effect of left-wing politics but right-wing economics, which will become a problem long-term.”

Still, Bo's verdict is unlikely to be a real deterrent to the rampant corruption Xi has sought to tackle, despite the party and state media playing up the angle that all are equal before the law.

“This case had little to do with corruption. It's a political case,” said Zhang Ming, a professor at Renmin University in Beijing.